What is CLV? And why is it important to calculate it?

Summary

Customer Lifetime Value (CLV or LTV) is an estimate, over a defined period, of what a customer can bring in.

In a subscription business, it’s a projection, over a limited period, of the number of subscribers and booking 📈. This is a calculation to be made each time my actions influence the number of subscribers, the Retention rate (RR%) and/or the average selling price (ASP).

Knowing the CLV of each change helps me make an informed decision about customer acquisition and retention strategies, marketing spend, and product development.

1. What is a CLV in real life?

The more transactions customers carry out with me, the more my booking increases, the more important these customers become.💶 As long as I keep my clients, I can capture part of their budget. These customers have a long-term value called Customer Lifetime Value (CLV).

Let’s take a simple example to understand the concept:

I sell baby diapers. Each baby will wear diapers until around 3 years old, 8 per day for the first few months and one per day for the last few months. On average this will be around 4 per day at € 0.50 each.

3 x 365 days x 4 diapers/days x € 0.50 = € 2190.

A baby has a CLV of € 2190 over 3 years. The CLV is calculated over 3 years since beyond that, the baby no longer wears a diaper, its value no longer increases.

Whatever my role is, I always have the same approach regarding CLV:

- If I sell only premium diapers, I seek to build customer loyalty to capture the maximum of the CLV. The customer must not go to competition.

- If I have a multi-brand approach, I seek to optimize the CLV upwards while planning a fallback offer. It’s better to keep a customer with a lower CLV than let him/her go to competition.

- If I operate the point of sale (POS), I try to increase CLV by selling peripheral products like baby food and avoid purchases at a competitor’s POS.

The CLV is a theoretical value; my goal is to capture it as much as possible while improving it. CLV improvements are made through cross-sell 🍼 🧸and up-sell .

2. What’s special about subscription’s CLV?

In a subscription business, the notion of recurrence is central: there’s an acquisition and renewals as long as the customer remains subscribed. I don’t know how long my customers will remain subscribed, I cannot calculate a precise CLV. However, I can use the CLV as a method of relative measurement between several options.

If I consider a change, I do an A/B test. With the test results of each tested scenario , I make a CLV calculation. The CLV of Control is my reference and I compare it to the CLV of each option.

Whenever I consider a change, I need to know its long-term impact. The CLV is a projection over 3 or 4 years in order to include the effects of several renewals.

3. When and how do I calculate a CLV?

I calculate the CLV each time I voluntarily decide on a change that affects one of the three parameters: the number of subscribers (subscribers), the retention rate (RR%) or the average selling price (ASP).

As I know the current values of these three parameters, I calculate a CLV including several renewals. This is my reference value.

Then, for each alternate scenario, I estimate variations on one or more of these three parameters. I get a CLV for each of these options.

I compare the effectiveness of my different strategies. Then, I can take an educated decision, based on tangible data, over the long term.

Still not convinced? Too abstract?

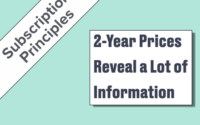

As in my previous article, I shown carried out a price elasticity test aiming to find out the optimum in acquisition.

Table #1: Results of an acquisition test

Challenger #2 is the best option for volume, Challenger #3 for booking. However, from Control to Challenger #3, we sacrifice nearly 600 units to gain only € 400.

Is this sacrifice profitable in the long term?

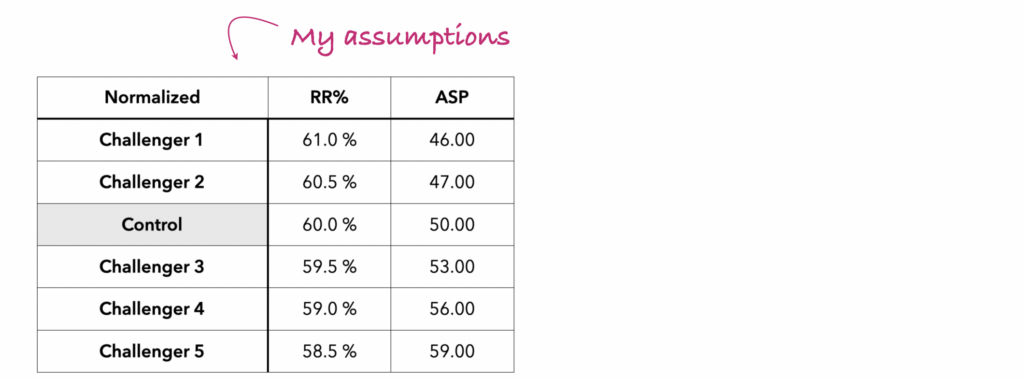

To answer this, I calculate the CLV over 3 years for each option according to the conditions in table #2 below:

The renewal price will be equal to acquisition price

My clients are very price sensitive, their retention rate varies by +0.5 points, when the price drops by €3 and -0.5 points when the price increases by €3

Table #2: RR% and ASP by product for next years

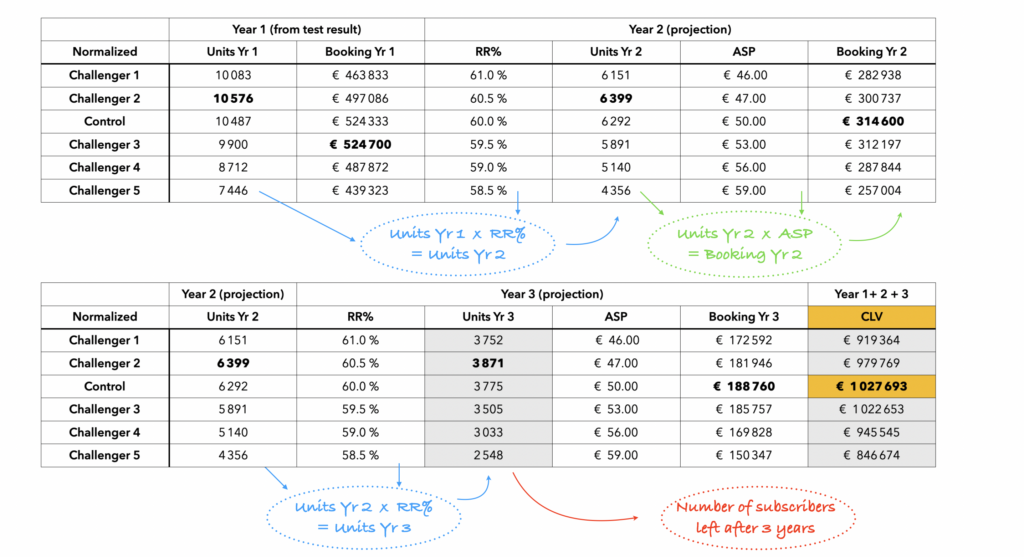

As initial values, I re-use the data (units and booking) from the acquisition test (table #1). Then, I use the above RR% and ASP for the subsequent years.

Table #3: Units & Booking each year.

In the last column of the table above, I read the CLV of each option which is the sum of the bookings over 3 years. The other grey column is interesting as it gives the number of subscribers left after 3 years.

Under the chosen conditions,

- Challenger #3 is better in acquisition (year 1) but not in the long term.

- Challenger #2 is the best option in volume due to a higher number of units associated with a higher conversion rate.

- Control is the best option in terms of booking. Compared to Challenger #2, we’re short of 100 units but made € 48k more.

If the ideal solution, where volume and booking increase, doesn’t present itself, it will be necessary to arbitrate between the two. In my Acquisition example (Table #1), Challenger #3 requires sacrificing 600 subscriptions for a gain of €400 or €0.66 per unit. If my cost of acquisition per unit is higher, then this option isn’t good.

Key Takeaways

- In a subscription business, a CLV calculation is crucial before making any changes affecting any of the 3 key parameters.

- A CLV should include all costs: for instance, before making a price increase, I must include additional costs at Customer Support due to increased number of calls or customer satisfaction score.

- A CLV calculation cannot be read absolutely or directly. For example, it’s necessary to validate that a sacrifice in units is worth the benefit in booking by comparing it to the cost of acquisition.